How to design a good digital user experience #1: the theory

Ever wondered why one website is easy to use whereas other sites only bring frustrations? Why you are happy to use that one particular app on a day-to-day basis and you would rather ignore other apps as much as possible? The thing is that, in most cases, the people that designed those practical and widely used products took the user’s needs and requirements to heart. As you will have noticed, far too often, a lot of websites and apps continue to sin against the basic rule of listening out to users’ needs. Which is why this practical guide is intended to help you avoid these frequently encountered mistakes in product design.

In the digital age, where AI and machine learning rule the roost, it is essential that we properly understand our users’ needs and behaviors. To do so, we need to take a closer look at human psychology. Having a better understanding of the human brain and human perception enables you to get a better idea of what goes on in the user’s mind and allows you to create more user-friendly products.

If only it was that easy for a UX or UI designer to simply consult a first year psychology student’s textbook. Alas! Whether or not a digital product is easy to use depends on many different factors. Which principles should you bear in mind to achieve that aim? Find out in this first blog post of the series and learn more about the theory.

What is usability?

First things first! If you have come across the word ‘usability’ before, you need to know that usability is all about whether or not a digital product is easy to use. ISO 9241-11 describes this as “the extent to which a software can be used by specified users to achieve specified goals with effectiveness, efficiency and satisfaction in a specified context of use.”

The main thing to remember is that all software we develop is developed for the people who will be using that software.

Which means that a good product needs to be:

- Easy to learn and easy to understand >> learnability

- Efficient so it is easy for the user to swiftly and effectively perform his duties >> efficiency

- A product for which the user does not need to make special efforts to remember the details of how it works >> memorability

- A product that responds to human input and provides feedback >> error tolerance

- Designed to deliver a pleasant experience that satisfies the user so they will want to use the product again next time >> satisfaction

Are you familiar with the 10 Usability heuristics?

Also try and take these 10 usability heuristics into account as widely as possible, and your design is all set to deliver a user-friendly experience.

- Make sure the status of the system is properly visible.

- Match the system to the real world needs of users by ensuring the system speaks the users’ language. Use words and concepts the user is familiar with. Observe real world conventions so that information is displayed in a natural and logical order sequence.

- Put the user in the driving seat, free to make the choices he/she wants to make.

- Be consistent and build on existing behavioral patterns and accepted best practices.

- Prevent the user from being able to make mistakes.

- See to it that users do not need to remember things.

- Deliver a product that is adaptable and efficient to use.

- Go for a minimalist design.

- Help users spot, notice and repair mistakes.

- Provide a helping hand by setting up ways to get in touch and/or a help feature.

How does cognitive psychology help you design better interfaces?

It is also good to have some understanding of the way the human brain works. If you are looking to create a product that is better geared to our users’ needs, it is important to understand a number of basic principles from a cognitive psychology angle. This is why we will have a closer look into Gestalt Theory below.

Gestalt theory was developed in the early part of the 20th century by Max Wertheimer. This psychological philosophy focuses on perception and observation by humans and the human brain. In a nutshell: the things our brain perceives when our senses become aware of them. This theory sets out on the assumption that man perceives more than merely the sum of the separate sensory stimuli.

“The whole is other than the sum of the parts.”

— Kurt Koffka, Psychologist & professor at University of Giessen

When we perceive complex elements as humans, we first see the whole before we discern the individual parts. For example: when you look at someone’s face, it is the human face as a whole you see first - not a separate pair of eyes, a nose and a mouth. Understanding these psychological principles enables you to take them into account more consciously during the design stage.

In 1923, Max Wertheimer described a number of basic principles or laws that show how the human mind tends to perceive visual stimuli. These five Gestalt laws are the ones that are most relevant to designers.

- Law of Proximity

This law states that when we perceive elements that are close to each other, we perceive those elements as a single group. Translated to the design of apps and websites, this means that a clear structure and visual hierarchy is less straining on users, enabling them to quickly identify things and respond as appropriate. We've already talked about this in a previous (graphic) design blog post.

The example below shows five standalone rectangles, yet the human brain will perceive them as a single group.

Positioning two rectangles at a slightly greater distance away suddenly changes our perception, making us see two groups instead. To the brain, this makes it difficult to continue to see the 5 rectangles as a group.

The same principle applies when we are designing an interface, particularly when it comes to the spacing of text and typography. The spacing between the text and the title is very important in this respect. If positioned incorrectly, the whole will be perceived as illogical.

- Law of Similarity

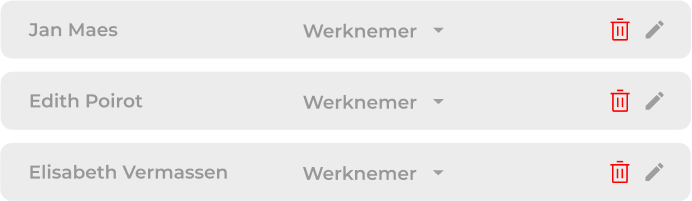

This law states that we group elements together based on what they look like. This means that, as humans, we perceive elements that look alike as a single group. This also means that elements that have the same functionality, meaning and level within a hierarchical relation need to visually match up.

The example below again shows 5 rectangles. Only this time, two of the rectangles have rounded corners. Our brain simply groups them together by type. So we are instinctively making a distinction between the rounded rectangles and the non-rounded rectangles.

In interface design too, this principle matters. Consistent successions of actions should be a requirement in comparable situations; identical terminology should be used in prompts, menus and help screens. In addition, it is best to maintain consistency in the use of colors, lay-out, capital letters, fonts, etc.

- Law of Closure

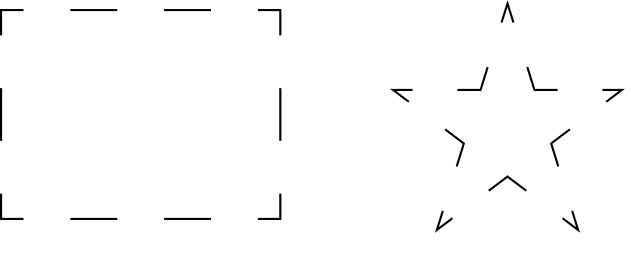

When the brain comes across a complex element from which a component is missing or where the pattern is interrupted, our brain instinctively fills the gaps.

Take a look at this example.

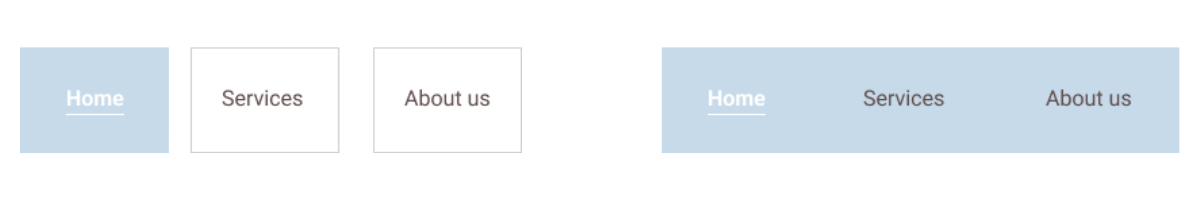

- Law of Continuity

Our brain is inclined to see objects that are arranged in lines or on curves as related or grouped. This is because objects that are connected by straight or curved lines are seen in a way that follows the smoothest path.

Comparing the examples of menus shown below makes it clear that the menu bar on the right is easier to scan and comprehend than the menu bar on the left.

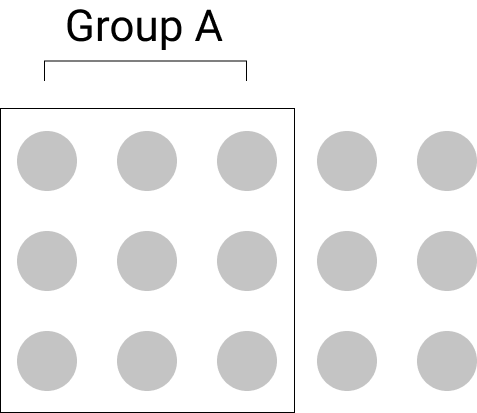

- Law of common region

This principle is strongly related to proximity. It states that when elements are located inside one and the same closed off area, we will perceive them as a single group. You have elements positioned together, but draw a boundary around them that singles them out as a specific area and we will perceive them as a separate group.

In UI design, we are familiar with this law, especially in the use of cards. When using cards, what you are actually doing is creating a boundary around a number of elements, thereby showing that all elements inside the card belong to the same area of information, even if other information is seen nearby.

Conclusion

When it comes to design, we use a lot of different theoretical principles, but we do not always do so consciously. As a UX or UI expert, it is important to be aware of this. The usability principles and Gestalt psychology as explained above can certainly help to improve the user experience of your product, even though there are lots of other psychological theories that can help you with the process of creating a better design. So keep your eyes and ears wide open!

Expect a second tip in the next blog post, in which we'll be looking into how to make an interface more straightforward and more focused.

Read all articles in this blog series:

- Tip 1: Fill your backpack with theory

- Tip 2: Instill focus and simplicity in interfaces (coming soon)

- Tip 3: Be aware of the importance of the most common interface elements (coming soon)

- Tip 4: Design interfaces for all users (coming soon)

- Tip 5: Gain a better understanding of your users by involving them (coming soon)

Looking for high-quality UX and UI design? Let us help you and take a look at what we offer!

In order to view this content, you need to accept Marketing & third party cookies.

Click here to adjust your preferences